- Home

- A. C. H. Smith

Labyrinth

Labyrinth Read online

A.C.H. Smith

Contents

Cover

Chapter One - The White Owl

Chapter Two - What's Said Is Said

Chapter Three - Pipsqueak

Chapter Four - Which Is Which

Chapter Five - Bad Memories

Chapter Six - Up and Up

Chapter Seven - The Meaning of Life

Chapter Eight - A Very Loud Voice

Chapter Nine - Another Door Opens

Chapter Ten - No Problem

Chapter Eleven - Windows in the Wilderness

Chapter Twelve - And No Birds Sing

Chapter Thirteen - Once Bitten

Chapter Fourteen - O Body Swayed to Music

Chapter Fifteen - The Time of Her Life

Chapter Sixteen - The Gates of Goblin City

Chapter Seventeen - Saints and Whiskers

Chapter Eighteen - Seeming

Chapter Nineteen - Good Night

Movie Stills

Back Cover

Chapter One - The White Owl

Nobody saw the owl, white in the moonlight, black against the stars, nobody heard him as he glided over on silent wings of velvet. The owl saw and heard everything.

He settled in a tree, his claws hooked on a branch, and he stared at the girl in the glade below. The wind moaned, rocking the branch, scudding low clouds across the evening sky. It lifted the hair of the girl. The owl was watching her, with his round, dark eyes.

The girl moved slowly from the trees toward the middle of the glade, where a pool glimmered. She was concentrating. Each deliberate step took her nearer to her purpose. Her hands were open, and held slightly in front of her. The wind sighed again in the trees. It blew her cloak tightly against her slender figure, and rustled her hair around her wide-eyed face. Her lips were parted.

“Give me the child,” Sarah said, in a voice that was low, but firm with the courage her quest needed. She halted, her hands still held out. “Give me the child,” she repeated. “Through dangers untold and hardships unnumbered, I have fought my way here to the castle beyond the Goblin City, to take back the child you have stolen.” She bit her lip and continued, “For my will is as strong as yours … and my kingdom as great …”

She closed her eyes tightly. Thunder rumbled. The owl blinked, once.

“My will is as strong as yours.” Sarah spoke with even more intensity now. “And my kingdom as great …” She frowned, and her shoulders dropped.

“Oh, damn,” she muttered.

Reaching under her cloak, she brought out a book. Its title was The Labyrinth. Holding the book up before her, she read aloud from it. In the fading light, it was not easy to make out the words. “You have no power over me …”

She got no further. Another clap of thunder, nearer this time, made her jump. It also alarmed a big, shaggy sheepdog, who had not minded sitting by the pool and being admonished by Sarah, but who now decided that it was time to go home, and said so with several sharp barks.

Sarah held her cloak around her. It did not give her much warmth, being no more than an old curtain, cut down, and fastened at the neck by a glass brooch. She ignored Merlin, the sheepdog, while concentrating on learning the speech in the book. “You have no power over me,” she whispered. She closed her eyes again and repeated the phrase several times.

A clock above the little pavilion in the park chimed seven times and penetrated Sarah’s concentration. She stared at Merlin. “Oh, no,” she said. “I don’t believe it. That was seven, wasn’t it?”

Merlin stood up and shook himself, sensing that some more interesting action was due. Sarah turned and ran. Merlin followed. The thunderclouds splattered them both with large drops of rain.

The owl had watched it all. When Sarah and Merlin left the park, he sat still on his branch, in no hurry to follow them. This was his time of day. He knew what he wanted. An owl is born with all his questions answered.

All the way down the street, which was lined on both sides with privet-hedged Victorian houses similar to her own, Sarah was muttering to herself, “It’s not fair, it’s not fair.” The mutter had turned to a gasp by the time she came within sight of her home. Merlin, having bounded along with her on his shaggy paws, was wheezing, too. His mistress, who normally moved at a gentle, dreamy pace, had this odd habit of liking to sprint home from the park in the evening. Perhaps that owl had something to do with it. Merlin was not sure. He didn’t like the owl, he knew that.

“It’s not fair.” Sarah was close to sobbing. The world at large was not fair, hardly ever, but in particular her stepmother was ruthlessly not fair to her. There she stood now, in the front doorway of the house, all dressed up in that frightful, dark blue evening gown of hers, the fur coat left open to reveal the low cut of the neckline, the awful necklace vulgarly winking above her freckled breast, and — wouldn’t you know? — she was looking at her watch. Not just looking at it but staring at it, to make good and sure that Sarah would feel guilty before she was accused, again.

As Sarah came to a halt on the path in the front garden, she could hear her baby brother, Toby, bawling inside the house. He was her half brother really, but she did not call him that, not since her school friend Alice had asked, “What’s the other half of him, then?” and Sarah had been unable to think of an answer. “Half nothing-to-do-with-me.” That was no good. It wasn’t true, either. Sometimes she felt fiercely protective of Toby, wanted to dress him up and carry him in her arms and take him away from all this, to a better place, a fairer world, an island somewhere, perhaps. At other times — and this was one — she hated Toby, who had twice as many parents in attendance on him as she had. When she hated Toby, it frightened her, because it led her into thinking about how she could hurt him. There must be something wrong with me, she would reflect, that I can even think of hurting someone I dote upon; or is it that there is something wrong in doting upon someone I hate? She wished she had a friend who would understand the dilemma, and maybe explain it to her, but there was no one. Her friends at school would think her a witch if she even mentioned the idea of hurting Toby, and as for her father, it would frighten him even more than it frightened Sarah herself. So she kept the perplexity well hidden.

Sarah stood before her stepmother and deliberately held her head high. “I’m sorry,” she said, in a bored voice, to show that she wasn’t sorry at all, and anyway, it was unnecessary to make a thing out of it.

“Well,” her stepmother told her, “don’t stand out there in the rain. Come on.” She stood aside, to make room for Sarah to pass her in the doorway, and she glanced again at her wristwatch.

Sarah made a point of never touching her stepmother, not even brushing against her clothes. She edged inside close to the door frame. Merlin started to follow her.

“Not the dog,” her stepmother said.

“But it’s pouring.”

Her stepmother wagged her finger at Merlin, twice. “In the garage, you,” she commanded. “Go on.”

Merlin dropped his head and loped around the side of the house. Sarah watched him go and bit her lip. Why, she wondered for the trillionth time, does my stepmother always have to put on this performance when they go out in the evening. It was so hammy — that was one of Sarah’s favorite words, since she had heard her mother’s co-star, Jeremy, use it to put down another actor in the play they were doing — such a rag-bag of over-the-top clichés. She remembered how Jeremy had sounded French when he said clichés, thrilling her with his sophistication. Why couldn’t her stepmother find a new way into the part? Oh, she loved the way in which Jeremy talked about other actors. She was determined to become an actress herself, so that she could talk like that all the time. Her father seldom talked at all about people at his office, and when he did it was dreary in compariso

n.

Her stepmother closed the front door, looking at her watch once more, took a deep breath, and started one of her clichéd speeches. “Sarah, you’re an hour late …”

Sarah opened her mouth, but her stepmother cut her off, with a little, humorless smile.

“Please let me finish, Sarah. Your father and I go out very rarely —”

“You go out every weekend,” Sarah interrupted rapidly.

Her stepmother ignored that. “— and I ask you to babysit only if it won’t interfere with your plans.”

“How would you know?” Sarah had half turned away, so as not to flatter her stepmother with her attention, and was busy with putting her book on the hall stand, unclipping her brooch, and folding the cloak over her arm. “You don’t know what my plans are. You don’t even ask me.” She glanced at her own face in the mirror of the hall stand, checking that her expression was cool and poised, not over the top. She liked the clothes she was wearing: a cream-colored shirt with full sleeves, a brocaded waistcoat loosely over the shirt, blue jeans, and a leather belt. She turned even further away from her stepmother, to check on how her shirt hung from her breasts down to her waist. She tucked it in a little at the belt, to make it tighter.

Her stepmother was watching her coldly. “I am assuming you would tell me if you had a date. I would like it if you had a date. A fifteen-year-old girl should have dates.”

Well, Sarah was thinking, if I did have a date you are the last person I would tell. What a hammy — no, tacky — view of life you do have. She smiled grimly to herself. Perhaps I will have a date, she thought, perhaps I will, but you will not like it, not one bit, when you see who’s dating me. I doubt you will see him. All you will know about it is hearing the front door shut behind me, and you will sneak to the window, as you always do, and poke your nose between those horrid phony-lace curtains you put up there, and you will see the tail lights of a wicked dove-gray limousine vanishing around the corner. And after that, you will keep seeing pictures in the magazines of the two of us together in Bermuda, and St. Tropez, and Benares. And there will be nothing at all you can possibly do about it, for all your firm views on bedtimes and developmental psychology and my duties and rolling up the toothpaste tube from the bottom. Oh, stepmother, you are going to be sorry when you read in Vogue about the cosmic cash that Hollywood producers are offering us for — Sarah’s father came down the stairs into the hall. In his arms he was carrying Toby, clad in red-and-white striped pajamas. He patted the baby’s back.

“Oh, Sarah,” he said mildly, “you’re here at last. We were worried about you.”

“Oh, leave me alone!” Afraid that she might be close to tears, Sarah gave them no chance to reason with her. She ran upstairs. They were always so reasonable, particularly her father, so long-suffering and mild with her, so utterly convinced that they were always obviously in the right, and that it was only a matter of time before she consented to do as they wished. Why did her father always take that woman’s side? Her mother never wore that look of pained tolerance. She was a woman who could shout and laugh and hug you and slap you all within a minute or two. When she and Sarah had a quarrel, it was an explosion. Five minutes later, it was forgotten.

In the hallway, her stepmother had sat down, still in her fur coat. Wearily, she was saying, “I don’t know what to do anymore. She treats me like the wicked stepmother in a fairy tale, no matter what I say. I have tried, Robert.”

“Well …” Sarah’s father patted Toby thoughtfully. “It is hard to have your mother walk out on you at that age. At any age, I suppose.”

“That’s what you always say. And of course you’re right. But will she never change?”

Holding Toby in one arm, Robert patted his wife on the shoulder. “I’ll go and talk to her.”

Thunder rumbled again. A squall of raindrops clattered on the windows.

Sarah was in her room. It was the only safe place in the world. She made a point of going all around it each day, checking that everything was just where it had been and should be. Although her stepmother seldom came in there, except to deliver some ironed clothes or to give Sarah a message, she was not to be trusted. It would be typical of her to take it into her head to dust the room, even though Sarah made sure that it was kept clean, and then she would be bound to move things around and not put them back where they belonged. It was essential to ward off that disturbing spirit.

All the books had to remain in the proper positions, in alphabetical order by author and, within each author’s group, in order of acquisition. Other shelves were filled with toys and dolls, and they were positioned according to affinities known only to Sarah. The curtains had to hang exactly so that, when Sarah was lying on her bed, they symmetrically framed the second poplar tree in a line that she could see from the window. The wastepaper basket stood so that its base just touched the edge of one particular block on the parquet floor. It would be unsafe if these things were not so. Once disorder set in, and the room would never be familiar again. People talked about how upsetting it was to be burgled, and Sarah knew just how it must feel, as though some uncaring stranger were fooling around with your most precious soul. The woman who came in to clean three times a week knew that she was never to do anything to this room. Sarah looked after everything in there herself. She had learned how to fix electric plugs, and tighten screws, and hang pictures, so that her father should have no need to come in except to speak to her.

Sarah was now standing in the middle of her room. Her eyes were red. She sniffled, and chewed her lower lip. Then she walked over to her dressing table and gazed at a framed photograph. Her father and mother, and herself, aged ten, gazed back at her. Her parents’ smiles were confident. Her own face in the photograph was, she thought, slightly over the top, grinning too keenly.

All around the room, other eyes watched. Photographs and posters displayed her mother in various costumes, for various parts. Clippings from Variety were taped to the mirror of the dressing table, praising her mother’s performances or announcing others she would give. On the wall beside the bed was pinned a poster advertising her latest play; in the picture, Sarah’s mother and her co-star, Jeremy, were cheek to cheek, their arms around each other, smiling confidently. The photographer had lit the pair beautifully, showing her to be so pretty, he so handsome, with his blond hair and a golden chain around his neck. Beneath the picture was a quote from one of the theater critics: “I have seldom felt such warmth irradiating an audience.” The poster was signed, with large flourishing signatures: “For Darling Sarah, with all my love, Mom,” and, in a different hand, “All Good Wishes, Sarah — Jeremy.” Near the poster were more press clippings, from different newspapers, arranged in chronological order. In them, the two stars could be seen dining together in restaurants, drinking together at parties, and laughing together in a little rowboat. The texts were all on the theme of “Romancing on and off the stage.”

Still sniffling from time to time, Sarah went to the small table beside her bed and picked up the music box her mother had given her for her fifteenth birthday. The memory of that gorgeous day was still vivid. A taxi had been sent for her in the morning, but instead of going to her mother’s place it had taken her along the waterfront to where Jeremy and her mother were waiting in Jeremy’s old black Mercedes. They went out into the country for lunch beside a swimming pool at some club where Jeremy was a member and the waiters spoke French, and later, in the pool, Jeremy had clowned around, pretending to drown, to such an effect that an elderly man had rung the alarm bell. They had giggled all the way back to town. At her mother’s place, Sarah was given Jeremy’s present, an evening gown in pale blue. She wore it to go with them to a new musical that evening, and afterward to supper, in a dimly lit restaurant. Jeremy was wickedly funny about every member of the cast they had seen in the musical. Sarah’s mother had pretended to disapprove of his scandalous gossip, but that had only made Sarah and Jeremy laugh more uncontrollably, and soon all three of them had tears in th

eir eyes. Jeremy had danced with Sarah, smiling down at her. He kidded her that a flashbulb meant that they’d be all over the gossip columns next morning, and all the way home he drove fast, to shake off the photographers, he claimed, grinning. As they said good night, her mother gave Sarah a little parcel, wrapped in silver paper and tied with a pale blue bow. Back in her room, Sarah had unwrapped it, and found the music box.

The tune of “Greensleeves” tinkled, and a little dancer in a frilly pink dress twirled pirouettes. Sarah watched it reverently, until it became slow and jerky in motion. Then she put it down, and quietly recited from a poem she had studied in her English class:

“O body swayed to music, O brightening glance, How can we know the dancer from the dance?”

It was so easy to learn poetry by heart. She never had any difficulty in remembering those lines, whenever she opened the music box. In fact, she reflected, it’s easier to remember them than to forget them. So why was she having such trouble in learning the speech from The Labyrinth? It was only a game she was playing. No one was waiting for her to rehearse it, no audience, except Merlin, would judge her performance of it. It should have been a piece of cake. She frowned. How could she ever hope to go on stage if she could not remember one speech?

She tried again. “Through dangers untold and hardships unnumbered, I have fought my way here to the castle beyond the Goblin City, to take back the child you have stolen …” She paused, her eyes on the poster of her mother in Jeremy’s arms, and decided it would help her performance if she prepared for it. If you’re going to get into a part, her mother had told her, you’ve got to have the right prop. Costume and makeup and wigs — they were more for the actor’s benefit than for the audience’s. They helped you escape from your own life and find your way into the part, as Jeremy said. And after each show, you take it all off, and you’ve wiped the slate clean. Every day was a fresh start. You could invent yourself again. Sarah took a lipstick from the drawer in her dressing table, put a little on her lips, and rolled them together, as her mother did. Her face close the mirror, she applied a little more to the corners of her mouth.

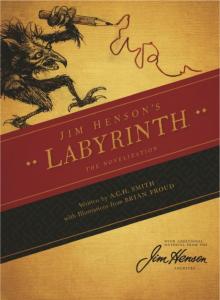

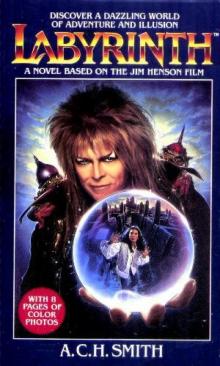

Labyrinth the Novelization

Labyrinth the Novelization Labyrinth

Labyrinth